Malformation, Malposition of Female Reproductive Organs and Menstrual Irregularities and DUB

Subject: Gynecological Nursing

Overview

Malformation of the Female External Genetalia

The Mulleria ducts' aberrant development, fusion, or resorption throughout fetal life causes congenital uterine abnormalities. These defects have been linked to a higher likelihood of preterm birth, miscarriage, and other bad fetal outcomes. neither fixed nor fixed in size or shape. During pregnancy, it's common to have irregular myometrial contractions as well as changes to the size and position of the uterus.

Imperforate Hymen

Imperforate hymen is a frequent condition that can be acquired by inflammatory blockage following perforation or might be congenital. A rare congenital vaginal deformity known as an imperforate hymen involves the hymen covering the whole vaginal entrance.

The prevalence rates for females range from 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000. When the sinovaginal bulb fails to canalize with the remaining vagina, it happens. The irregular occurrence usually manifests as delayed menarche, cyclic lower abdomen pain and mass, and bulging vaginal membrane at the vaginal introitus. These symptoms are brought on by the buildup of menstrual blood as hematocolpos and hematometra above the imperforate hymen. Pelvic infection with tubo-ovarian infection is one of the described odd ways of presentations of the sequelae of untreated imperforate hymen.

Other reported bizarre modes of presentations of the complications of untreated imperforate hymen that include pelvic infection with tubo-ovarian abscess, obstructive acute renal failure, non-urological urine retention, hematosalpinx, peritonitis, endometriosis, mucometrocolpos, constipation and recurrent urinary tract infection.

In infants, the absence of a mucus trail at the posterior commissure of the labia majora or the presence of a bulging hymen can be used to diagnose an imperforate hymen. The diagnosis of an imperforate hymen can also be confirmed with the help of transabdominal and transrectal ultrasounds. The accumulation of hydrocolpos or mucocolpos in the female fetus as a result of maternal oestrogens can also be seen as a bulging imperforate hymen on an antenatal ultrasound.

The only effective treatment for an imperforate hymen is surgical removal of the hymen from the base and evacuation of the uterus and vagina of any stored menstrual blood. When virginity is to be preserved, hymenotomy can only be performed on the center section of the hymen.

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Transverse vaginal septa, a rare form of mullerian abnormality, are caused by the vaginal plate and the caudal end of the mullerian ducts failing to fuse or canalize. Primary amenorrhea, stomach pain, and hematocolpos are the most prevalent imperforate septa symptoms in adolescence. Perforate septa can present in adolescence or early adulthood and present with a more varied presentation that is typically linked to the foreshortened vagina. Clinical examination and imaging, typically magnetic resonance imaging, are used to make a proper diagnosis (MRI). The surgical management, which includes vaginal and abdominoperineal operations, is greatly influenced by the thickness and placement of the septum. Vaginal stenosis and re-obstruction are long-term side effects that may necessitate further surgery.

Vaginal Atresia

A congenital abnormality known as vaginal atresia causes obstruction of the uterovaginal outflow canal. It happens when the urogenital sinus, which contributes to the caudal section of the vagina, fails to form. Fibrous tissue has taken the place of the caudal region of the vagina. A well-differentiated uterus is seen in the fibrous tissue of the lower vagina.

Symptoms

- Dyspareunia

- Dysmenorrhea

- Oligomenorrhoea and with complete obstruction.

- Amenorrhoea are the common complaints. This last symptom may bring the patient to the antenatal clinic.

- Obstruction to the free flow of menses causes severe attacks of monthly pain. Recurrent colic with amenorrhoea is an invariable feature of cases of complete atresial obstruction.

- On occasion, periodic rectal bleeding is the predominant symptom. Bizarre symptoms suggesting frustration are often noted.

Clinical Types

- Minor Atresia: This affects the middle strait and comprises over 90% of cases presenting at hospital; of these 7% are imperforate.

- Imperforate: Here rectal bimanual examination reveals an enlarged cystic uterus showing irritability. Often there are quite marked intermittent contractions noted on palpation. There is monthly colic. Many suggest they are pregnant.

- Perforate: The patient seeks help because of dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and sterility. Upon examination, a vagina 1+ inches long and shaped like a pyramid is found. The apex has noticeable scarring and induration. The menstrual products normally leave through a tiny opening that rarely allows the finest probe to enter without exerting force. It frequently occupies a lateral location and signifies the continued existence of the lateral channel. Menstruation alone is the sole thing that keeps the track open. If the narrow tube is successfully navigated, a long-lasting flow of a dark brown, viscous fluid results. This is as a result of the upper genital tract constantly having some level of retention.

- Major Atresia: In major atresia, there is complete absence of the lower two-thirds of the vagina. A haematometra (rarely a pyometra) is present. Once again, there are two forms: most are imperforate and a few are perforated.

- a. Imperforate: An examination per rectum reveals a fibrous cord replacing the vagina; thecervix can be detected and the ballooned-out upper portion of the vagina, above which the distended uterus can be felt. The upper inch of the vagina is patent owing to the presence of the cervix and the constant lochial flow after delivery which flushes the saline Noxa into the lower part of the canal.

- b. Perforate: Rarely, the recto-vaginal septum is eroded by ulceration in the upper third of the vagina and a fistulous communication with the rectum proceeds. Here, the chief complaint is the periodic rectal blood loss; despite the communication with the rectum only rarely does pyometra supervene. On proctoscopic examination, the orifice of the fistula is minute and difficult to detect t that the patient may have to be recalled when menstruation has set in. Often fine radiating striae producing a stellate effect indicate the site of the communication with the vagina. If the terminal three inches of an eight-inch probe be bent to an angle of it may be passed into hat 45 deg the uterus and the tip palpated through the abdominal wall for the cervix is always dilated in these cases.

Treatment

By using surgery, very satisfactory results can be attained. Thankfully, most mid-strait septa can be quickly eased. A small probe is used to explore the septum, which should be perforated. Larger instruments are then used until the point of a mosquito forceps may be used. The held products are allowed to flow away once they are opened up to widen the aperture. The septum is now ballooned out by the upper vagina being packed tightly through the hole created by the paraffin gauze. Since the septum's perimeter is now clearly defined, it can be neatly circumcised. After inserting a metal catheter into the bladder and a size 20 Hegar's dilator into the rectum to serve as guides, a passage is dissected up to the cervix uteri in cases of complete atresia. The development of a neovagina is also a part of vaginal agenesis.

Malformation of Cervix and Uterus

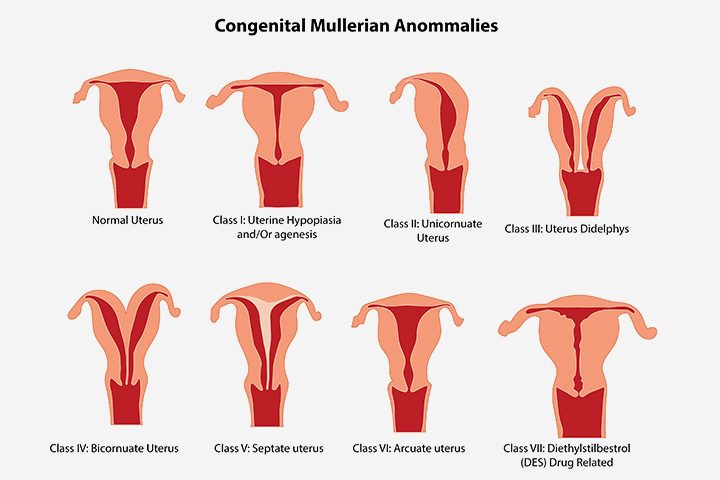

Uterine anomalies have been divided into 7 types by the American Fertility Society (1988). This classification is based on the developmental problem responsible for the irregular shape. Uterine anomalies may result from 3 mechanisms:

- Stage 1: failure of one or both of the 2 mullerian ducts to form.

- Stage 2: failure of the 2 ducts to fuse completely.

- Stage 3: failure of the 2 fused mullerian ducts to dissolve the septum that results from fusion.

Clinical Presentation

- Menstrual dysfunction

- Pain

- Infertility and

- Fetal wastage

- Obstetric complications

- Renal anomalies, other anomalies in fetus

American Fertility Society Classification Scheme - 7

- Hypoplasia/Agenesis

- Unicornuate Uterus

- Didelphys Uterus

- Bicornuate Uterus

- Septare Uterus

- Arcuate Uterus

- DES-related anomaly also includes creation of a neovagina.

Failure to Form

1. Hypoplasia/Agenesis

A woman may be born without a cervix, fallopian tubes, a vagina, or even the complete vagina and uterus. The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus that opens into the vagina (except for the fundus). This is brought on by a developmental issue with a portion of each mullerian duct.

Because the tissues that give rise to the urinary tract are located close to the mullerian ducts and are impacted by the same harmful shock, these anomalies are frequently linked to urinary tract anomalies.

2. Unicornuate Uterus

A single-horn (banana-shaped) uterus arises from the healthy mullerian duct when one of the mullerian ducts fails to mature. This uterus with one horn might be the only one. However, the residual mullerian duct may create an imperfect (rudimentary) horn in 65% of women with unicornuate uteri.

There may or may not be a cavity in this primitive horn, but either way, there is no entrance that connects to the unicornuate uterus and vagina.

There is a chance that a pregnancy will develop in this primitive horn, however 90% of such pregnancies rupture due to space restrictions.

Failure to Fuse

1. Didelphys Uterus

A single-horn (banana-shaped) uterus arises from the healthy mullerian duct when one of the mullerian ducts fails to mature. This uterus with one horn might be the only one. However, the residual mullerian duct may create an imperfect (rudimentary) horn in 65% of women with unicornuate uteri.

There may or may not be a cavity in this primitive horn, but either way, there is no entrance that connects to the unicornuate uterus and vagina.

There is a chance that a pregnancy will develop in this primitive horn, however 90% of such pregnancies rupture due to space restrictions.

2. Bicornuate Uterus

The majority of congenital uterine anomalies (45%) occur in this way. It happens as a result of the "top" müllerian ducts failing to fuse. This failure could be "total," leaving one cervix shared by two independent single-horn uterine bodies.

A "partial" bicornuate uterus, on the other hand, had the müllerian ducts fused at the "bottom" but not the "top." As a result, there is only one uterine cavity and one cervix at the base, but at the top, it divides into two different horns. These 2 horns are distinct structures when viewed from the exterior of the uterus because the ducts never joined at the top.

Preterm birth and mispresentation are both frequent throughout pregnancy.

Failure to Dissolve Septum

1. Septate Uterus

A defect in stage 2 or 3 of uterine development leads to a septate uterus. The normal fusion of the two Müllerian ducts. The deterioration of the median septum, however, failed.

In the event that this failure was "total," the uterus as a whole still has a median septum, which divides the uterine cavity into two single-horned uteri that share a cervix.

If this failure was "partial," the median septum's bottom portion reabsorbed in stage 2, while its top failed to disintegrate in stage 3. As a result, the uterine cavity and cervix are both present at the bottom, but at the top, they are divided into two different horns.

The exterior shape of the uterus is a single unit that seems normal since this uterine abnormality develops later in the uterine development process, after complete duct fusion. This is distinct from the bicornuate uterus, which, when viewed from the outside, seems to branch into two distinct horns.

Preterm birth and mispresentation are both frequent throughout pregnancy.

2. Arcuate Uterus

Essentially typical in shape, this type of uterus has a slight midline indentation in the uterine fundus from incomplete dissolution of the median septum. Because it does not appear to have any harmful effects on pregnancy in terms of premature labor or malpresentation, it is assigned a separate categorization.

3. DES Uterus

Daughters of mothers who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy are more likely to develop clear cell vaginal cancer and uterine abnormalities.

50% have cervical defects, such as an incompletely formed cervix that predisposes to cervical insufficiency, and two-thirds have abnormalities, such as a small, incompletely formed uterus ("hypoplastic") and/or a T-shaped hollow. It is unknown how DES interferes with normal uterine development.

Diagnosis

- Physical examination

- Ultrasonography

- MRI

- Laproscopy

Treatment

- Surgical intervention depends on the extent of the individual problem.

- With a didelphic uterus surgery is not usually recommended.

- A septate vagina and the rudimentary horn of a bicornuate uterus are usually removed.

- Uterine reconstruction is recommended for a bicornuate or septate uterus which is considered to be the cause of recurrent miscarriages.

Malposition of the uterus

- Ante- toward the front of the body (toward the pubic bone)

- Retro - toward the back of the body (toward the sacrum)

- Version - cervix / cervical axis of the uterus pulled/pointed

- Flexion - uterine fundus pulled/folded

- Anteversion - uterus and cervical axis oriented toward the pubic bone

- Anteversion and anteflexion - a combination of the above

- Retroversion - uterus and cervical axis oriented toward the sacrum

- Retroflexion - uterus oriented toward the sacrum, with the anterior portion of uterus convex

- Retroversion and retroflexion - a combination of the above

- Retrocessed - top and bottom of uterus are pushed toward the sacrum

- Anteflexion - uterus oriented toward the pubic bone, with the anterior portion of uterus concave

- Midposition/Vertical - uterus points straight upward toward the diaphragm

Retroversion of Uterus

Definition

When a woman's uterus (womb) tilts backward rather than forward, it is said to be retroverted. Commonly referred to as a "tipped uterus

Uterine retroversion occurs in roughly 15% of pregnant women. By 14 weeks, when the gravid uterus has grown into the abdominal cavity, retroversion typically resolves on its own. Very rarely, the uterus grows retroverted and settles into the pelvic cavity.

Causes

- Retroversion of the uterus is common. One in five women has this condition.

- The problem may also occur due to weakening of the pelvic ligaments at the time of menopause.

- An enlarged uterus can also be caused by pregnancy or a tumor. Scar tissue in the pelvis (pelvic adhesions) can also hold the uterus in a retroverted position.

- Scarring may come from:

- Endometriosis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Pelvic surgery

Symptoms

- Retroversion of the uterus almost never causes any symptoms.

- Rarely, it may cause pain or discomfort. Some women do not experience any symptoms.

However, the primary symptoms of a tipped uterus are:

- Pain during sexual intercourse or dyspareunia.

- Pain during menstruation or dysmenorrhea.

Other symptoms may include:

- Back pain during intercourse

- Urinary tract infections

- Difficulty using tampons

- Minor incontinence

- Fertility problems

On examination and investigation

An examination of the pelvis will reveal the position thought to be a pelvic tumor or a developing fibroid. To identify the uterus, perform a rectovaginal exam. A tipped uterus, however, can occasionally be somewhere in between a mass and a retroverted uterus. The precise location of the uterus can be determined through an ultrasound examination.

Possible Complications

Atypical positioning of the uterus may be caused by endometriosis, salpingitis or pressure from a growing tumor.

Treatment

Treatment is not needed most of the time. Underlying disorders, such as endometriosis or

adhesions should be treated as needed. There is no way to prevent the problem. Early treatment of PID or endometriosis may reduce the chances of a change in the position of the uterus.

Retroflexion of the uterus

When compared to a normal uterus, a retroflexed uterus is orientated in a backward-tilting manner. Also known as a retroverted or pointed uterus. Instead of tilting toward the bladder in this situation, the top of the uterus points towards the back of the pelvic area.

Causes

Pregnancy and complication from endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease/salpingitis, multiparty, lack of abdominal muscle tone, genetics, abdominal surgeries including cesarean section which cause scarring and weigh or pull the uterus into a position.

Symptoms

Painful intercourse and menstruation are the most common symptoms. There may also be back pain during menstruation or intercourse. Urinary tract infections and minor incontinence might also be experienced.

Treatment

Treat the possible causes of the retroflexed uterus could very well treat its malposition. Thus, treating endometriosis or fibroids or improving muscle tone or encouraging weight loss could very well encourage the uterus into a more mid-line or anterior position.

Treatment options include special exercises, surgery and a pessary.

- Surgery is used to suspend a retroflexed uterus, relieving some pain during sex or menstruation. It is generally used only when there are also other problems, such as endometriosis.

- Knee-chest position, for ten minutes, three times per day.

- Kegel's exercises can strengthen the pelvic floor, then the theory transfers further into a strong pelvic floor supporting overall pelvic muscles and appropriate pelvic ligament alignment. For months at a time, women used to wear pessaries similar to those worn by women with uterine or bladder prolapse to encourage the forward movement of the anterior uterine wall.

Abmormal Menstrual Bleeding

This is used to describe bleeding that differs from the regular menstrual cycle (in terms of the amoun duration or interval). Young adolescents and women between the ages of 45 and 50 frequently experience irregular menstrual cycles and bleeding. Investigation may not reveal any causes because the ovaries and the pituitary that controls them are still developing. Bleeding could be minor or life-threatening. There are numerous causes, some of which may be patient age-related. Bleeding after menopause is referred to as vaginal. The identified reason is the focus of treatment.

Causes

Young Adolescents

- Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

- Complications of pregnancy

- Coital lacerations including rape and defilement

- Accidental traumatic lesions of vulva and vagina

Women of Child Bearing Age

- Complications of pregnancy, including ectopic pregnancy and Choriocarcinoma

- Coital lacerations

- Use of hormonal methods of contraception or intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD)

- Cervical cancer

- Fibroids

- Dysfunctional bleeding

Peri-Menopausal Women

- Dysfunctional bleeding

- No cause may be found on investigation as it is mostly due to aging of the ovaries.

- All other causes listed for women of childbearing age also apply in post-menopausal women.

- Pelvic cancers such as cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, vaginal or vulva cancer and ovarian tumours, withdrawal from oestrogen therapy.

- Coital tears

- Urethral caruncle

- Atrophic vaginitis/endometritis

- Occasionally bleeding from the rectum and urethra may be confused with genital tract bleeding,

Investigations

- FBC, platelet count, sickling

- Blood clotting screen e.g. Prothrombin time, INR

- Pelvic ultrasound scan (to rule out pelvic lesions)

- Urine analysis

- Diagnostic dilatation and curettage (D & C) for women of child bearing age and postmenopausal women.

Treatment

Treatment objectives

-

To find the cause of bleeding

-

To stop the bleeding

-

To replace the blood loss

Non-pharmacological treatment

- Vaginal coital tear suturing in theatre

- Inevitable or incomplete abortion-uterine evacuation

- Refer pelvic cancers and other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding early to a gynaecologist for early detection. Treatment may involve radical surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Menstrual bleeding issues can reveal itself in a variety of ways.

Any departure from regular menstruation or a regular menstrual cycle pattern is referred to as abnormal uterine bleeding.

Regularity, frequency heaviness, and length of flow are the three main qualities, albeit each of these can vary greatly. International discussions are currently taking place about using more descriptive language.

The most common times for women to experience dysfunctional uterine hemorrhage are at the start and conclusion of their reproductive years. It affects up to 50% of women and is described as irregular, aberrant bleeding that happens without any discernible anatomic abnormality. It is linked to anovulatory cycles, which are frequent in the first year following menarche and as women get older and near menopause.

A hormonal imbalance is associated to the pathogenesis of DUB. In the early part of the menstrual cycle, estrogen levels rise as usual with anovulation. A corpus luteum does not form and progesterone is not generated in the absence of ovulation. As a result of entering a hyperproliferative condition, the endometrium eventually outgrows its estrogen supply. As a result, the endometrium sloughs irregularly and bleeds excessively. Anemia may develop if the bleeding is severe enough and persistent enough.

DUB is similar to several other types of uterine bleeding disorders and sometimes overlaps these conditions. They include:

- Menorrhagia (abnormally long, heavy periods)

- Oligomenorrhea (bleeding occurs at intervals of more than 35 days)

- Metrorrhagia (bleeding between periods)

- Menometrorrhagia (bleeding occurs at irregular intervals with heavy flow lasting more than 7 days)

- Polymenorrhea (too frequent periods)

Types of DUB

Anovular Bleeding

About 90% of DUB event occur when ovulation is not occuring (anovulatory DUB).

At the extremes of reproductive age, such as early puberty and perimenopause, anovulatory menstrual cycles are frequent. In such circumstances, women fail to produce and release a mature egg. This prevents the formation of the corpus luteum, a mound of progesterone-producing tissue. As a result, the uterine lining thickens excessively because estrogen is continuously produced. In this situation, the period is delayed, and when it does come, the menstrual cycle may be quite protracted and heavy. Sometimes there are several causes, and the patient's age may be one of them. When a woman starts to bleed after ceasing to have periods for six to twelve months or longer, this is referred to as postmenopausal bleeding. The mechanisms are typically unknown, though. The etiology can be psychological (stress), obesity, exercise, neoplasm or it may be idiopathic.

Ovulatory Bleeding/ Ovulatory DUB

10% of instances involve ovulating women, however because estrogen levels are low, progesterone secretion is extended in these circumstances. the reasons for irregular uterine lining loss and bleeding in the back. Some research has linked ovulatory DUB to uterine blood vessels that are more brittle. It can be a sign of a potential endocrine disorder that causes menorrhagia or metrorrhagia.

Etiology

The possible causes of DUB may include:

- Adenomyosis

- Hormonal imbalance

- Intrauterine systems (IUS)

- Hypothyroidism

- Fibroid tumors

- Endometrial polyps or cancer

- Morbid obesity

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Pregnancy

- Endometriosis

- Steroid therapy

- Blood dyscrasias/clotting disorder

Treatment

- Mild cases: Control bleeding with Norethisterone acetate, oral, 5 mg 8 hourly for 10-12 days.

- Life threatening bleeding: Admit patient to hospital and resuscitate with IV fluids and possibly blood transfusion. Control bleeding with Oestrogen, oral, 1.25-2.5 mg daily for 10-12 days.

- When the bleeding is controlled continue treatment with Norethisterone, oral, 5 mg 8 hourly for 10-12 days or Medroxyprogesterone Acetate, oral, 5 mg 8 to 12 hourly for 10-12 days or low dose oral contraceptive pill for 3-6 cycles.

- NSAIDS: Inhibit prostaglandins in ovulatory menstrual cycles.

- Surgery options include hysterectomy, dilatation and curettage (D & C), and endometrial ablation if the patient does not improve with medicinal treatment.

- Another option to a hysterectomy is endometrial ablation. Laser, electrosurgery excision, freezing, hot fluid infusion, and thermal balloon ablation are some of the techniques utilized for ablation. After endometrial ablation, the majority of women experience reduced menstrual flow, and up to 50% no longer experience periods. The response to endometrial ablation is less common in younger women than in older ones.

- Hypermenorrhea is treated with hysterectomy, although pathology—typically adhesions, endometriosis, or fibroids—is best treated with laparoscopic hysterectomy.

.

Things to remember

Questions and Answers

Define Dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is described as abnormal uterine bleeding without any organic causes that is brought on by a hormone mechanism. Only after all other organic and structural causes of abnormal vaginal bleeding have been ruled out should DUB be diagnosed.

What are the treatment and management of malformation of uterus ?

Treatment and management

If the retroversion is asymptomatic, no management or treatment is required. Only once there are symptoms should the treatment start.

- Give the patient instructions on how to perform an exercise that involves knees to the chest or prone sleeping. These actions by themselves may result in spontaneous repositioning.

- The uterus is replaced bimanually by introducing a Hodge pessary into the vagina for repositioning if the patient complains of dyspareunia or backaches and the uterus is found to be retroverted.

- Surgery: These days, treating malposition with surgery is uncommon. But if any of the following circumstances exist, a patient is told to have surgery.

- Fixed retroversion

- Recurrence of symptoms after removal of pessary

- Tubo-ovarian mass or pelvic adhesion

What do you mean by abnormal uterine bleeding and also write some of its types or form ?

Menstruation begins in healthy women between the ages of 12 and 14 and lasts the entirety of the reproductive cycle, with the exception of pregnancy, which typically occurs between the ages of 50 and 55. The typical rhythm lasts 28 to 30 days, with flows lasting 4 to 6 days. An average amount of bleeding is 60ml. Here are some examples of anomalous bleedings:

- Oligomenorrhoea: Bleeding occurs at intervals of more than 35 days for more than 6 months and usually caused by a prolonged of the follicular phase.

- Polymenorrhoea: Bleeding occurs at an interval of fewer than 21 days and may be caused by a luteal phase defect.

- Menorrhagia: Bleeding occurs at normal intervals (21-35) but with a heavy menstrual flow (>80ml) and duration (<7days).

- Menometrorrhagia: Bleeding occurs at irregular, non-cyclic intervals and with heavy flow (>80ml) or duration (<7days).

- Metrorrhagia: Irregular bleeding occurs between ovulatory cycle.

- Amenorrhea: Menstrual bleeding is absent for 6months or more in a non-menopausal woman.

- Dysmenorrhea: Painful menstruation in a regular or irregular cycle.

- Dysfunctional uterine bleeding: Abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic diseases.

List the causes and clinical features of dysfunctional uterine bleeding?

Causes of Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Endocrine

- Cushing disease.

- Hypothalamic-pituitary axis infancy.

- Hyperprolactinemia.

- Hypothyroidism.

- Menopause.

- Obesity.

- Ovarian failing before its time.

- Ovarian polycystic disease

Infections

- Chlamydia

- Gonorrhea

- PID

Clinical Features

The most typical symptom of DUB is bleeding between periods. It could also happen throughout your menstrual cycle. In this instance, it might consist of:

- Severe bleeding during the period

- Hemorrhage with several or sizable clots

- Greater than seven-day-long bleeding

- Hemorrhage that takes place under 21 days after the previous cycle

Other typical DUB signs include:

- Spotting

- Between periods bleeding

- Breast sensitivity

- Bloating

- Sdizziness

- Sfainting

- Sweakness

- Reduced blood pressure

- Higher heart rate

- Light skin

- Pain

- Passing substantial clots

- Per hour, soak a pad

What are the causes and clinical features of malformation of uterus?

Causes:

- Development abnormalities

- Acquired:

- Puerperal retroversion is brought on by the uterus's expanding weight and the uterine wall's flexibility.

- Because of the uterine ligaments' fragility, there is uterine prolapse.

- Adhesion caused by inflammatory adnexal disorders.

- Ovarian cyst or uterine fibroid exert pressure and draw the uterus backward.

Clinical manifestation:

- Back pain during the premenstrual period brought on by pelvic venous congestion brought on by higher sections of the wide ligaments kinking.

- Pelvic pressure, lower abdominal pain, and dysmenorrhea.

- Prolapsed ovaries in the Douglas pouch causing dyspareunia.

- Constipation, rectal pressure, and bowel dysfunction

- Urinary paradoxical symptoms include incontinence, frequency, and urine retention.

- Bleeding during pregnancy or a possible sudden abortion.

- The external os may not be in the seminal pool in the vagina, which can lead to infertility.

- Acute anterior vaginal angulation.

Write about the treatment and management of dysfunctional uterine bleeding ?

Medical therapy options are discussed below:

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) suppress endometrial development, reestablish predictable bleeding patterns, decrease menstrual flow, and lower the risk of iron deficiency anemia.

OCPs can be used effectively in a cyclic or continuous regimen to control abnormal bleeding.

Acute episodes of heavy bleeding suggest an environment of prolonged estrogenic exposure and buildup of the lining. Bleeding usually is controlled within the first 24 hours, as the overgrown endometrium becomes pseudo decidualised. Seek alternate diagnosis if flow fails to abate in 24 hours.

The type of OCP and underlying patient factors may be important determinants of potential risk for complications associated with OCPs. Studies have shown an increased risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolic events (blood clots) associated with contraceptives that contain drospirenone as compared with those that contain levonorgestrel

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system is considered a first-line treatment for adolescents withheavy menstrualbleeding.

Estrogen

Estrogen alone, in high doses, is indicated in certain clinical situations.

Prolonged uterine bleeding suggests the epithelial lining of the cavity has become denuded over time. In this setting, a progestin is unlikely to control bleeding. Estrogen alone will induce a return to normal endometrial growth rapidly.

Hemorrhagic uterine bleeding requires high-dose estrogen therapy. If bleeding is not controlled within 12-24 hours, a D&C is indicated.

Beginning progestin therapy shortly after initiating estrogen therapy to prevent a subsequent bleeding episode from treatment with prolonged unopposed estrogen is wise.

Progestins

Chronic management of AUB requires episodic or continuous exposure to a progestin. In patients without contraindications, this is best accomplished with an oral contraceptive given the many additional benefits, including decreased dysmenorrhea, decreased blood loss, ovarian cancer prophylaxis, and decreased androgens.

In patients with a pill contraindication, cyclic progestin for 12 days per month using medroxyprogesterone acetate (10 mg/d) or norethindrone acetate (2.5-5 mg/d) provides predictable uterine withdrawal bleeding, but not contraception. Cyclic natural progesterone (200 mg/d) may be used in women susceptible to pregnancy, but may cause more drowsiness and does not decrease blood loss as much as a progestin.

In some women, including those who are unable to tolerate systemic progestins/progesterone or those who have contraindications to estrogen-containing agents, a progestin-secreting IUD may be considered that controls the endometrium via a local release of levonorgestrel, avoiding elevated systemic levels.

Anovulatory bleeding and bleeding disorders

On rare occasions, a young patient with anovulatory bleeding also might have a bleeding disorder. Desmopressin, a synthetic analog of arginine vasopressin, has been used as a last resort to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in patients with documented coagulation disorders. Treatment is followed by a rapid increase in von Willebrand factor and factor VIII, which lasts about 6 hours.

Surgical Care

Most cases of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) can be treated medically. Surgical measures are reserved for situations when medical therapy has failed or is contraindicated.

Dilation and Curettage

D&C is an appropriate diagnostic step in a patient who fails to respond to hormonal management. The addition of hysteroscopy will aid in the treatment of endometrial polyps or the performance of directed uterine biopsies. As a rule, apply D&C rarely for therapeutic use in AUB because it has not been shown to be very efficacious.

Hysterectomy

Abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy might be necessary for patients who have failed or declined hormonal therapy, have symptomatic anemia, and who experience a disruption in their quality of life from persistent, unscheduled bleeding.

Endometrial Ablation

Endometrial ablation is an alternative for those who wish to avoid hysterectomy or who are not candidates for major surgery. Ablation techniques are varied and can employ laser, rollerball, resectoscope, or thermal destructive modalities. Most of these procedures are associated with high patient satisfaction rates.

Pretreat the patient with an agent, such as leuprolide acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, or danazol, to thin the endometrium.

The ablation procedure is more conservative than hysterectomy and has a shorter recovery time. Some patients may have persistent bleeding and require repeat procedures or move on to hysterectomy. Rebreeding following ablation has raised concern about the possibility of an occult endometrial cancer developing within a pocket of the active endometrium. Few reported cases exist, but further studies are needed to quantify this risk.

© 2021 Saralmind. All Rights Reserved.

Login with google

Login with google